Jason Patterson is a Black history base artist, with a focus on the African American history of Maryland's Eastern Shore.

About the Artist

Jason Patterson’s work focuses on African American history and highlights the role the past has in cultivating our current political and social conditions in the United States. Patterson’s practice is heavily research-based, with the majority of his studio time dedicated to that research to ensure that the historical and social narratives presented are well represented. Patterson makes his physical work through soft pastel portraiture, woodworking and the recreation, or reimagining of historical documents. Patterson’s figurative work is based on archived images. The work emphasizes the original medium, making it clear to the viewer that these drawings were modeled after daguerreotypes, film, newspaper clippings, and digital images. The intent is to show that the way these images were originally created is just as important as the subject matter they represent. This work investigates the different ways images, in those varying forms, structure the way we visually comprehend our history and define our present. Patterson also focuses on woodworking and the fabrication and aesthetic reimagining of historical documents. Designing and building stylized wood frames to house his work, these frames are as much a part of the artwork as the portraits and papers within them. Each frame design references the graphic, interior, and architectural design of the subject matter’s time period. The creation of documents is a way to stimulate thought on the subjects the work covers and offers a visually pleasing vehicle through which to incorporate important text. In our culture, especially in public spaces, when a document or an image is framed it suggests importance. Often the history Patterson is highlighting isn’t given its correct context or due respect in mainstream histories. Jason Patterson’s work aims to change that. Jason Patterson (born Champaign, Illinois 1984) was recently the Frederick Douglass Visiting Fellow at the Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience, at Washington College. He is currently a board member of the Kent Cultural Alliance and a fellow with the Chesapeake Heartland: An African American Humanities Project. He lives and works in Chestertown, Maryland.Jason Patterson website On The Black History of Kent County & Washington College Jason Patterson website Main site

Featured Work

Photos

![This portrait of Rosa Parks was drawn after a cropping of a photograph taken of Mrs. Parks with Rep. Shirley Chisholm in 1968. That year, Chisholm became the first African American congresswoman. Parks was an open supporter of Chisholm’s congressional run as well as Chisholm’s presidential campaign in 1972. This is just one of Rosa Park’s overlooked social and political actions beyond her 1955 bus arrest in Montgomery, Alabama.

When we think of Parks’s narrative we think of an isolated incident that sparked the Civil Rights Movement, where a meek, older woman (Parks was actually only 42) was tired after a long day’s work and would just not get up. This narrative was, and is, a more palatable story. But this simplified narrative misrepresents Parks’s actions and what they meant in the American South in 1955. It’s easier for Parks to be mythologized as a quiet, non-activist, non-confrontational victim than the seasoned civil rights activist she was, long before her arrest.*

In the 1940s and 50s, Rosa and her husband Raymond Parks were active Alabama NAACP members. Not only was Parks the Montgomery chapter’s secretary, in 1948, she was elected NAACP secretary for the State of Alabama. Earlier, in 1944, Parks drove across the state to Addeville, Alabama where the young Black woman Recy Taylor was gang raped by six white men. The local police were not investigating the crime so Mrs. Parks was sent by the NAACP to be an investigator and advocate for Taylor. Before that, in the early 1930s, Rosa and Raymond were involved in the defense of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American boys and teens wrongly accused of raping a white woman in Scottsboro, Alabama. This would become a landmark case concerning racial injustice in the United States.**

These are just a few examples of what is missing in our general understanding of Rosa Parks’s legacy. This artwork references the fact that Parks spent most of her life living in Detroit. This is meant to acknowledge that Rosa Parks is a part of Detroit’s rich African American history—a subtle way to encourage the viewer to look into Rosa Parks’s true history and life. The hope is that viewers will wonder why she’s referred to as a “Detroiter" and then learn about why Mrs. Parks had to leave her home in the South, only one year after the end of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.***

[*For a first hand account for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, see: The Montgomery But Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, by Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, Edited by David J. Garrow, 1987 |

**To read about the Recy Taylor case, see: At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance–A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power, by Danielle L. McGuire, 2010 |

***For an in depth and complete biography of Rosa Louise McCauley Parks, see: The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, by Jeanne Theoharis, 2013]](/sites/default/files/styles/optimized/public/artist_work/images/Parks3.jpg?itok=e_-hQfe6)

Featured Work: Photos

Drawing after a Detail of a Carte-de-visite portrait of Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, Taken by George G. Rockwood, ca 1860s

Canvas: Soft pastel, charcoal & charcoal pencil on raw canvas, under clear leveling gel. Frame: Stained pine wood with Liberian flag and Black Eyed Susans. 40 x 40 inches

2020

Henry Highland Garnet Elementary School on Calvert Street in Chestertown was the elementary through high school for African American students in Kent County prior to integration. The school’s namesake, Henry Highland Garnet, was born a slave in Kent County, Maryland on December 23, 1815. Nine years later, Garnet was carried north by his parents to freedom in New York where he pursued an education. At the National Negro Convention held in Buffalo, NY in 1843, the then 27-year-old Presbyterian minister rattled the abolition establishment by sponsoring armed insurrection and underscoring the sentiment that the exploited Black people across the continent should “rather die freemen, than live to be slaves.”

By mid-century, Garnet became the founding president of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, an organization that waged international campaigns against human trafficking. During his tenure, Garnet traveled to the United Kingdom where he spoke widely against the practice of slavery. His collaborations throughout the Caribbean, Mexico, and South America expanded the meaning of emancipation.

Garnet was also a controversial proponent of Black immigration to other countries, such as Liberia in Africa. During the Civil War, Garnet recruited black soldiers to the Union Army, barely escaping a vengeful white mob during the New York Draft Riots of 1863. In 1865, Garnet made history when selected by President Lincoln as the first African American to deliver a sermon to the U.S. Congress after the passing of the 13th Amendment that gave African American men the right to vote.

In 1881, President James A. Garfield appointed Garnet to serve as U.S. Minister and Counsel General to Liberia (United States ambassador to Liberia), fulfilling his lifelong dream to travel to Africa. However, Garnet died on February 13, 1882, only a few months after his arrival. He was given a state funeral by the Liberian government.

Accompanying this framed portrait of Garnet, the Black Eyed Susans, Maryland’s state flower, represents Garnet’s birthplace and the Liberian flag represents his resting place.

For Sale

$4,000.00

Contact the artist to purchase this piece

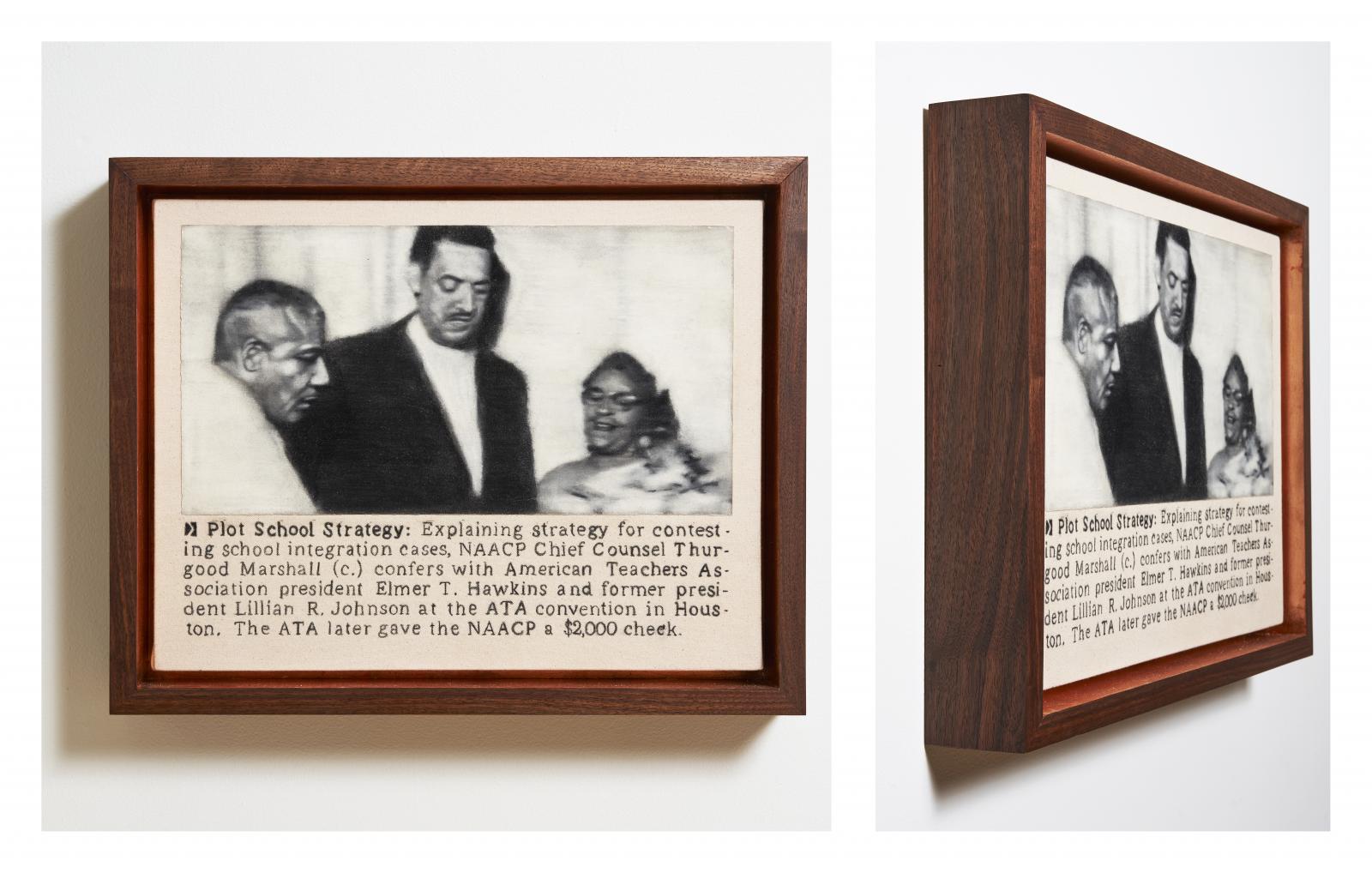

Drawing After a 1955 Jet Magazine Article Featuring American Teacher Association president Elmer T. Hawkins, former ATA President Lillian R. Johnson & Thurgood Marshall, then NAACP Chef Legal Council

Canvas: Soft pastel, charcoal & charcoal pencil on raw canvas, under clear leveling gel. Frame: Walnut & copper leaf. 25 x 20 in

2019

Elmer T. Hawkins was born in Catonsville, Maryland in 1904. Hawkins would go on to earn a bachelor's degree from Morgan State University in Baltimore in 1926. That same year Hawkins was hired as principal at the Henry Highland Garnet School in Chestertown, MD, the elementary through high school for Black children in Kent County during the segregated first half of the 20th century.

A decade later, Hawkins earned a master's degree from the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) and continued working toward a doctoral degree at several colleges and universities. Hawkins served as Garnet’s principal until the county’s school system was reformatted when Kent County integrated its schools, being the last county in Maryland to do so.

Throughout his tenure, Hawkins was a member of several educational and civic organizations. Perhaps the two roles of greatest prominence were his terms as the National Education Association’s Maryland Branch Director and the American Teachers Association President.

After the integration of Kent County schools, Hawkins served as the principal of Chestertown Middle School until his retirement in 1972. Hawkins died the next year and was recognized by the community for the transformative work he did in education and particularly for the county’s African American children.

This image was drawn after a clipping from a 1955 issue of Jet Magazine, covering the American Teachers Association’s convention that year, which was during Hawkins’ time as the ATA president. Along with Lillian R. Johnson, the ATA’s former president, Hawkins is pictured with NAACP lead legal council Thurgood Marshall who would go on to become the first African American Supreme Court Justice.

Rosa Parks, Detroiter

Canvas: Soft pastel on raw canvas, under clear leveling gel, with vintage paper mounted on canvas. Frame: Composite gold leaf on cherry wood.

2021

This portrait of Rosa Parks was drawn after a cropping of a photograph taken of Mrs. Parks with Rep. Shirley Chisholm in 1968. That year, Chisholm became the first African American congresswoman. Parks was an open supporter of Chisholm’s congressional run as well as Chisholm’s presidential campaign in 1972. This is just one of Rosa Park’s overlooked social and political actions beyond her 1955 bus arrest in Montgomery, Alabama.

When we think of Parks’s narrative we think of an isolated incident that sparked the Civil Rights Movement, where a meek, older woman (Parks was actually only 42) was tired after a long day’s work and would just not get up. This narrative was, and is, a more palatable story. But this simplified narrative misrepresents Parks’s actions and what they meant in the American South in 1955. It’s easier for Parks to be mythologized as a quiet, non-activist, non-confrontational victim than the seasoned civil rights activist she was, long before her arrest.*

In the 1940s and 50s, Rosa and her husband Raymond Parks were active Alabama NAACP members. Not only was Parks the Montgomery chapter’s secretary, in 1948, she was elected NAACP secretary for the State of Alabama. Earlier, in 1944, Parks drove across the state to Addeville, Alabama where the young Black woman Recy Taylor was gang raped by six white men. The local police were not investigating the crime so Mrs. Parks was sent by the NAACP to be an investigator and advocate for Taylor. Before that, in the early 1930s, Rosa and Raymond were involved in the defense of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American boys and teens wrongly accused of raping a white woman in Scottsboro, Alabama. This would become a landmark case concerning racial injustice in the United States.**

These are just a few examples of what is missing in our general understanding of Rosa Parks’s legacy. This artwork references the fact that Parks spent most of her life living in Detroit. This is meant to acknowledge that Rosa Parks is a part of Detroit’s rich African American history—a subtle way to encourage the viewer to look into Rosa Parks’s true history and life. The hope is that viewers will wonder why she’s referred to as a “Detroiter" and then learn about why Mrs. Parks had to leave her home in the South, only one year after the end of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.***

[*For a first hand account for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, see: The Montgomery But Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, by Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, Edited by David J. Garrow, 1987 |

**To read about the Recy Taylor case, see: At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance–A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power, by Danielle L. McGuire, 2010 |

***For an in depth and complete biography of Rosa Louise McCauley Parks, see: The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, by Jeanne Theoharis, 2013]

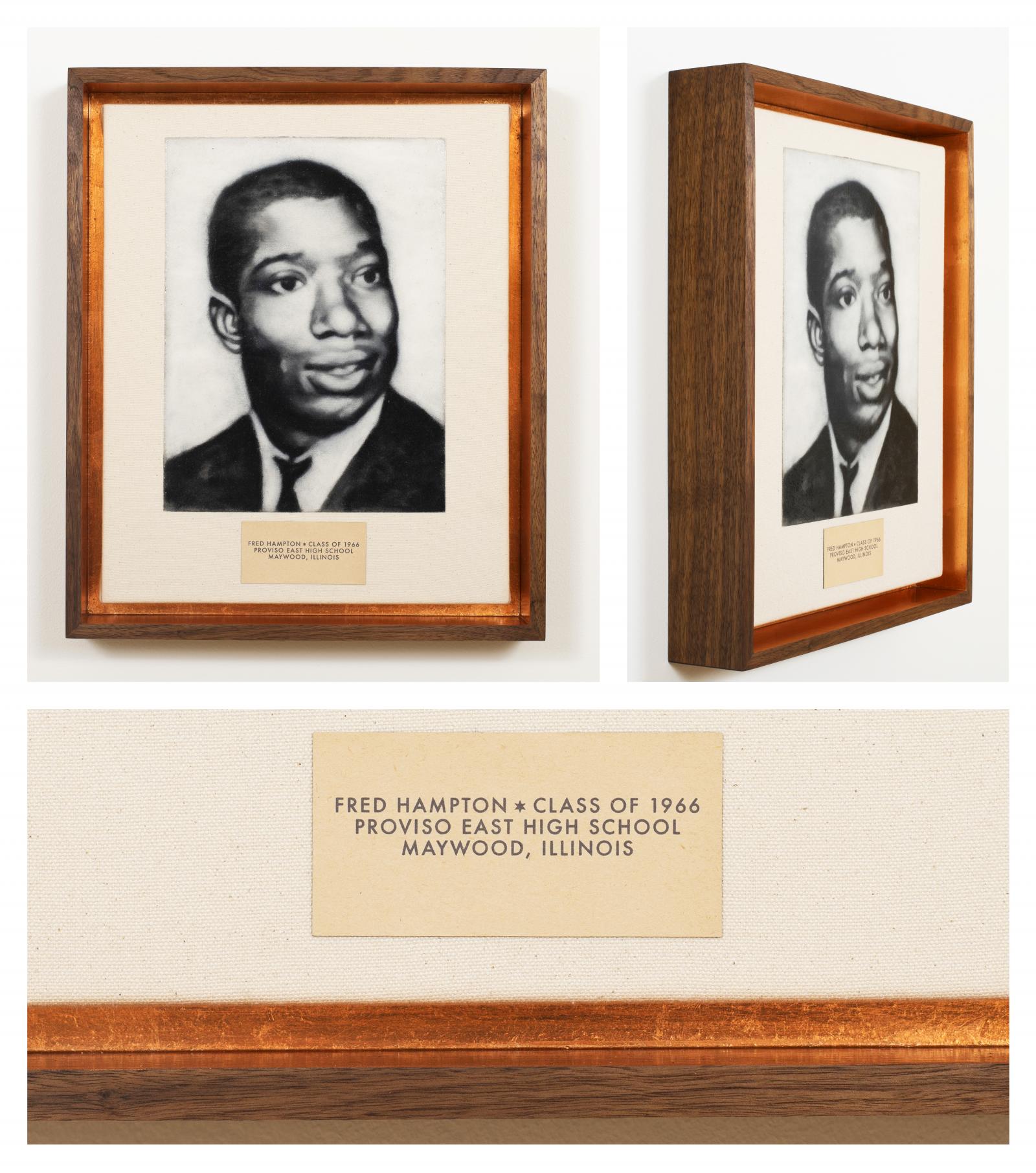

Fred Hampton, 1966

Canvas: Soft pastel on raw canvas, under clear leveling gel, with vintage paper mounted on canvas. Frame: Copper leaf on walnut wood.

2021

Fred Hampton grew up in Maywood, Illinois, just twenty minutes west of Chicago’s downtown. Fred excelled in high school and became a leader in his community at a young age. At 14, he began the local youth chapter of the NAACP. As he got older, Hampton became disillusioned by the NAACP and the mainstream civil rights movement’s more compromising approach to social change. Fred became more radicalized and militant, being greatly influenced by Malcolm X. In 1968, Hampton and others (including current congressman Bobby Rush) would establish the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party on Chicago’s west side.

Uniquely, as chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, Fred focused on cross-community organizing. He brokered peace among Chicago street gangs and created alliances with other race-based radical groups within the city, like the white Young Patriots and the Puerto Rican Young Lords, forming a “Rainbow Coalition.” Hampton and the Panthers organized free breakfasts for impoverished children and offered political science classes for the community. The Panthers also pushed back intensely against the overtly racist Chicago Police Department and Cook County State’s Attorney’s office, insisting on the self-policing of their communities.

In December of 1969, through a coordinated effort by the CPD, the state’s attorney, and the FBI, Hampton was killed in a police raid at his apartment. 14 years later, the US 7th Circuit Appeals Court acknowledged the illegality of the raid and forced the city, county, and federal government to agree to a 1.85 million dollar settlement.

This year (2021), the Shaka King film, Judas and the Black Messiah, was released. The biographical drama centers on Fred and William O’Neal, the Black Panther Party member and Fred’s bodyguard, who was also the FBI informant that helped the Chicago PD and FBI carry out the raid that ended Fred’s life. Hopefully this film will introduce more Americans to Fred Hampton. This portrait is meant to do the same. The choice to use Hampton’s high school senior photo, a contrast to later images of him, that are in the aesthetic of a revolutionary, was made to highlight his youth. Fred was only 21 when he was killed, just 3 years after 1966, when this photo was taken. It is amazing what Hampton was able to do in those 3 short years, and it is troubling to think of what more he could have accomplished in the decades that followed had he have lived.