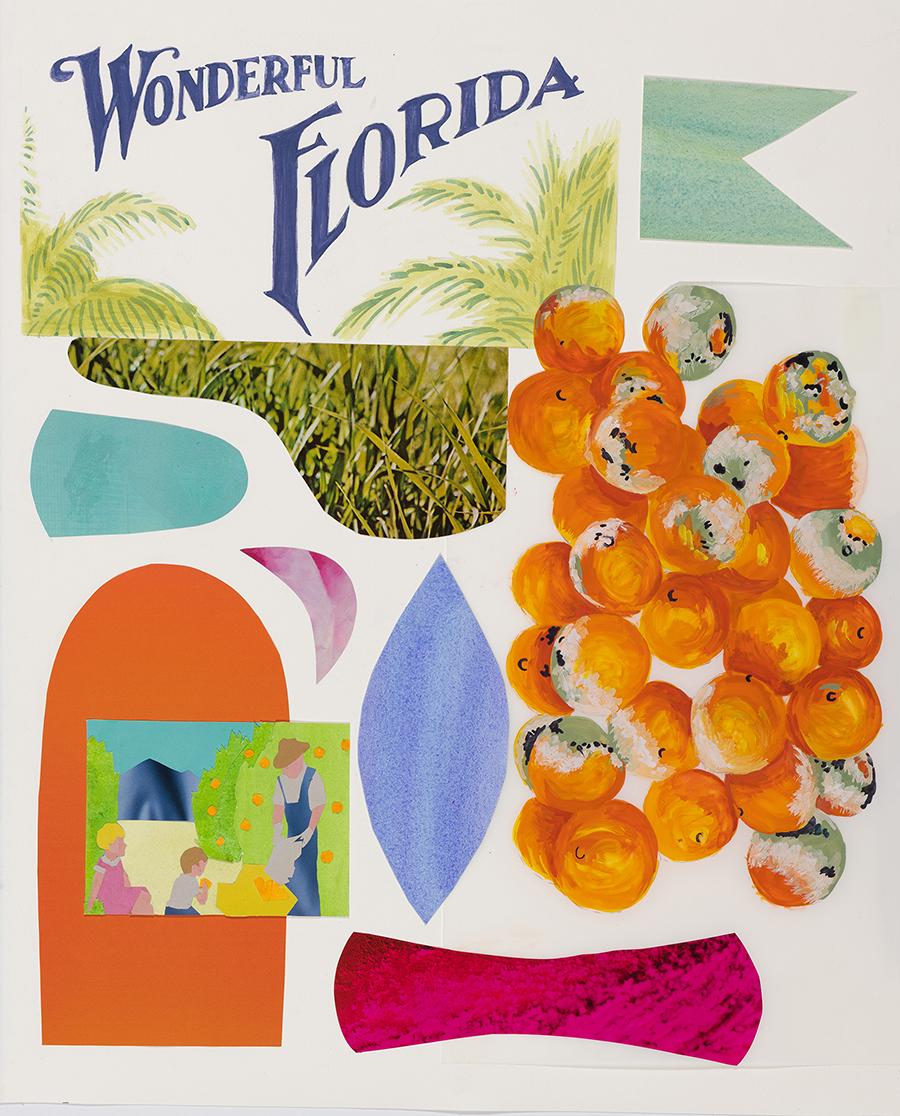

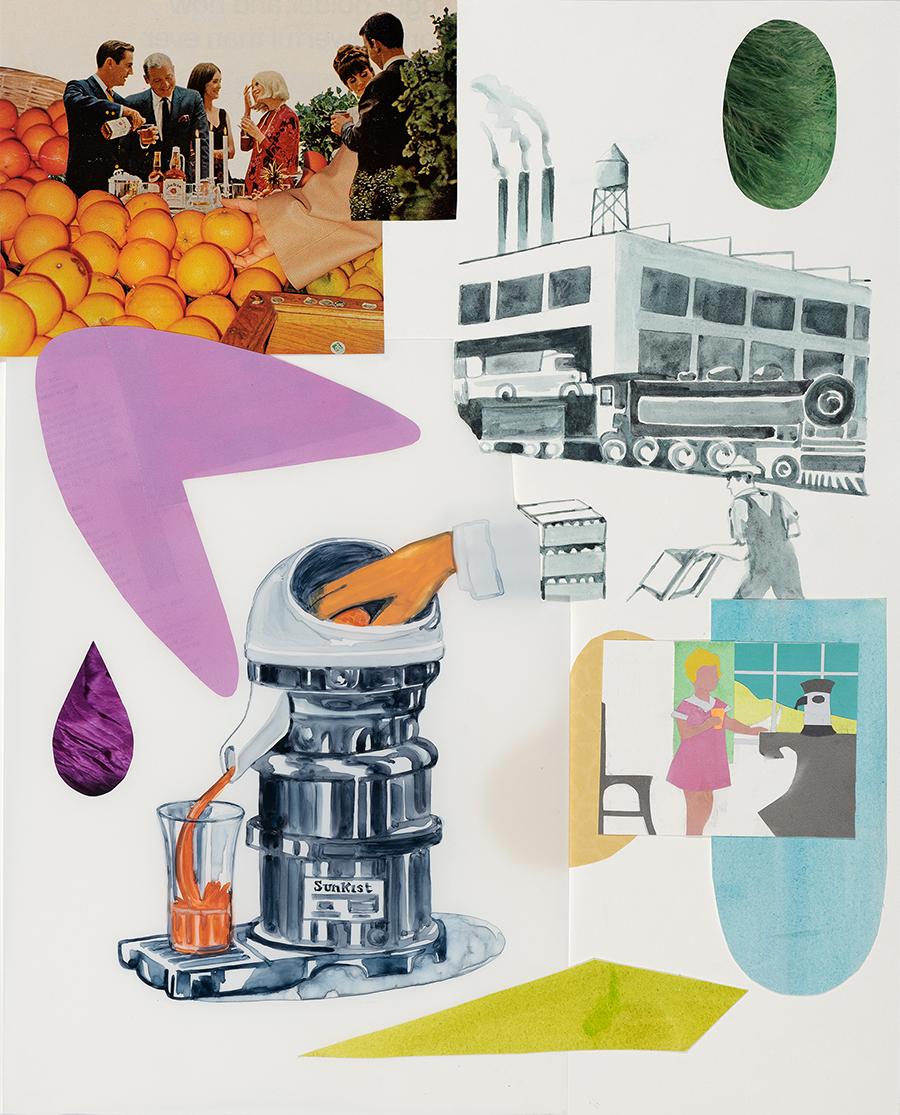

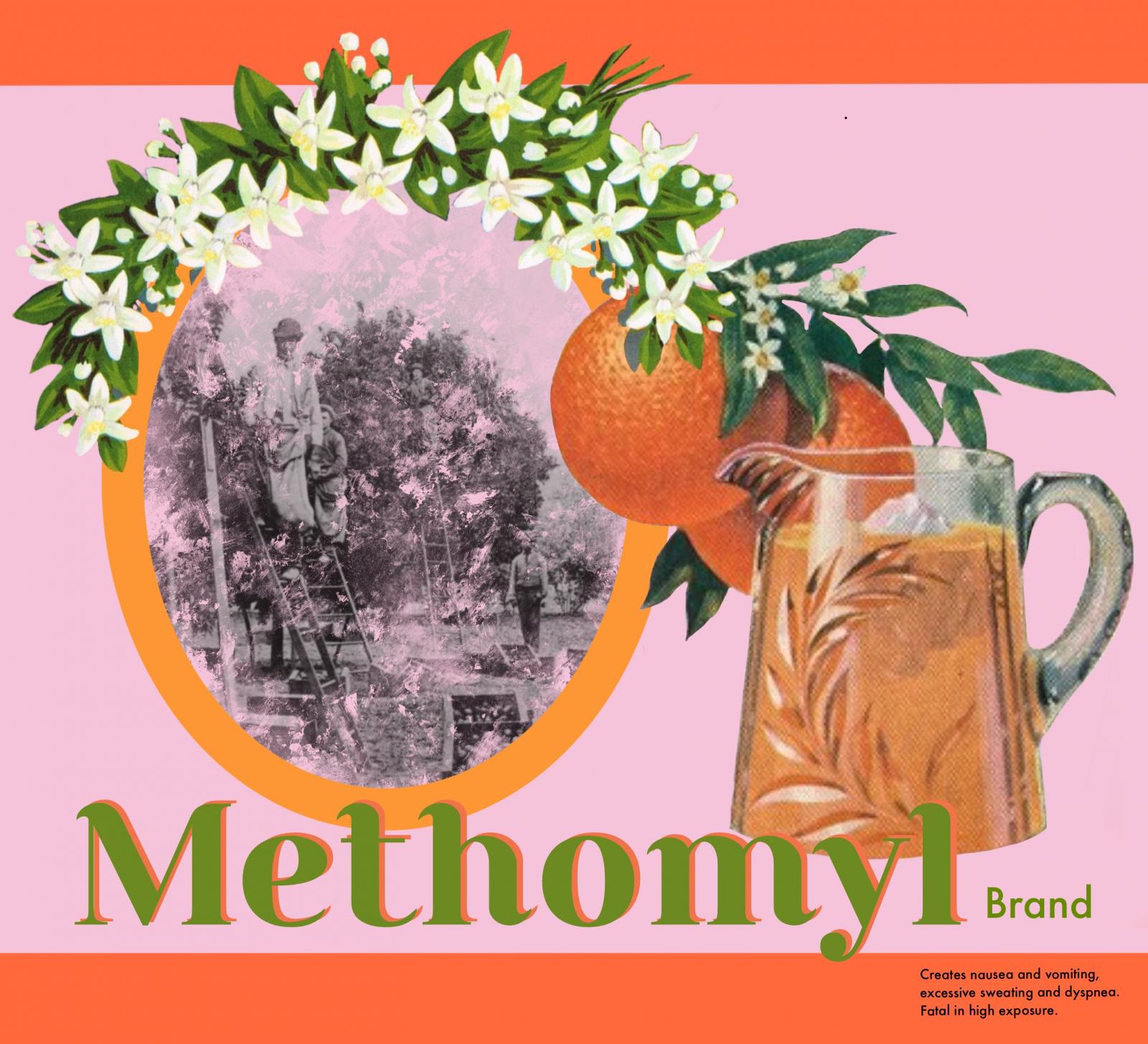

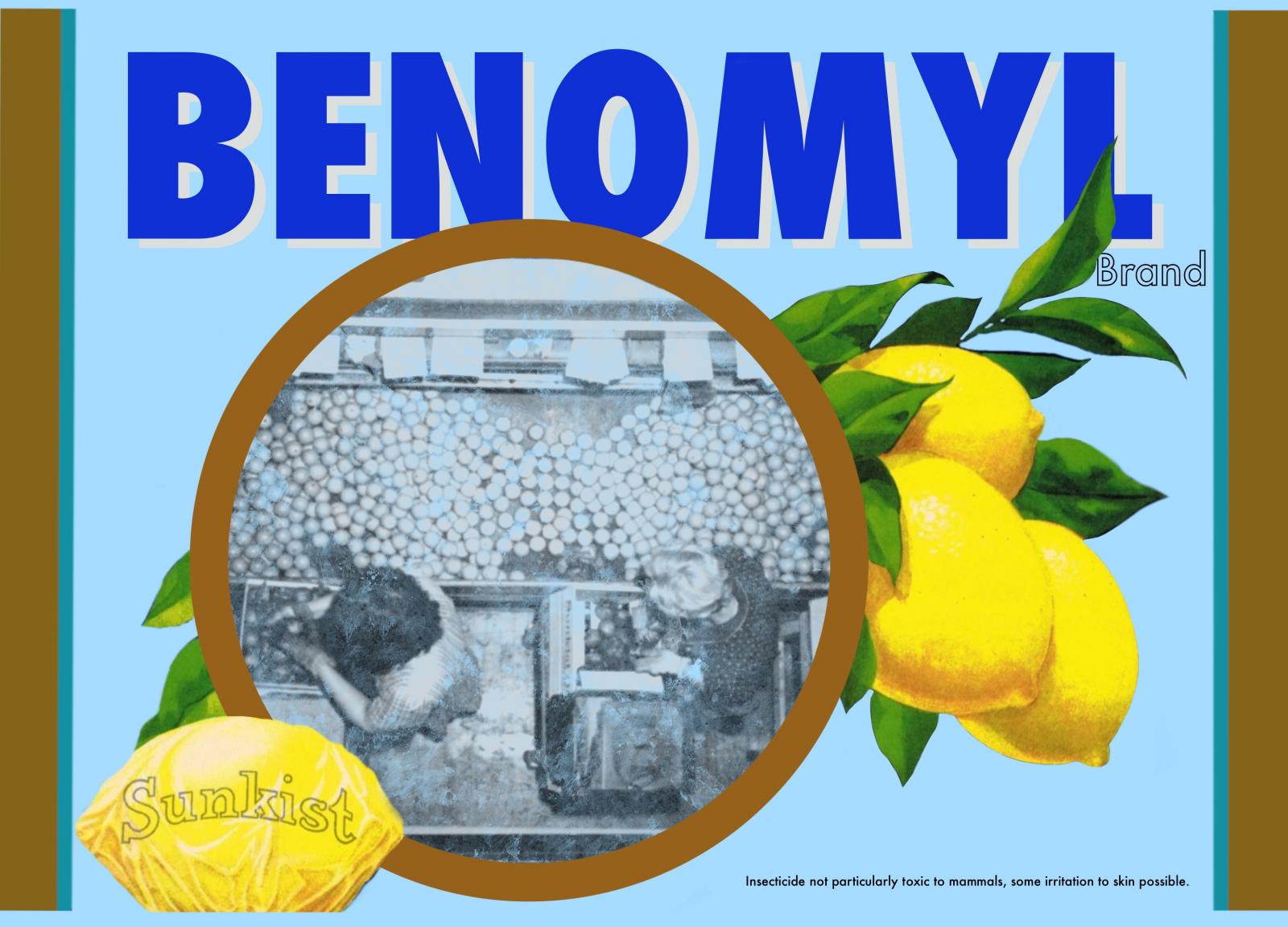

In my research-based multidisciplinary work, I unpack the hidden history of everyday American leisure culture. In watercolors, collage work, digital illustrations, ceramics and site-specific vinyl installations, I probe mythology erected by advertising, contrasting facade with fact, sometimes within a single work. Immersed as a child in 1990s Silicon Valley, a place split between the primordial past and a technological future, my today work evokes a secondhand nostalgia for the built landscape Americans construct and soon cast aside. My recent work investigates citrus, a national symbol of bounty and a shorthand for vacation with its sinister labor history and ecological effects.

About the Artist

Suzy Kopf is a multidisciplinary artist who scrutinizes the paper ephemera of midcentury consumer culture to magnify the enduring mythos of the American Dream. Through watercolor paintings, collages, and mixed-media installations she excavates archival materials and inherited nostalgia for failed utopias. Suzy has received numerous residency fellowships including Kala and PLAYA. Projects have been funded most recently by the Hagley Museum and the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). Suzy has exhibited in group and solo shows throughout the United States and Canada including the Delaware Contemporary, Spring/Break Art Fair and the Austrian Embassy. She is a 2023 fellow at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation in Upperville, VA. Suzy holds an MFA from MICA.Suzy Kopf website View Website Suzy Kopf website Purchase Art

Featured Work

Photos